Description

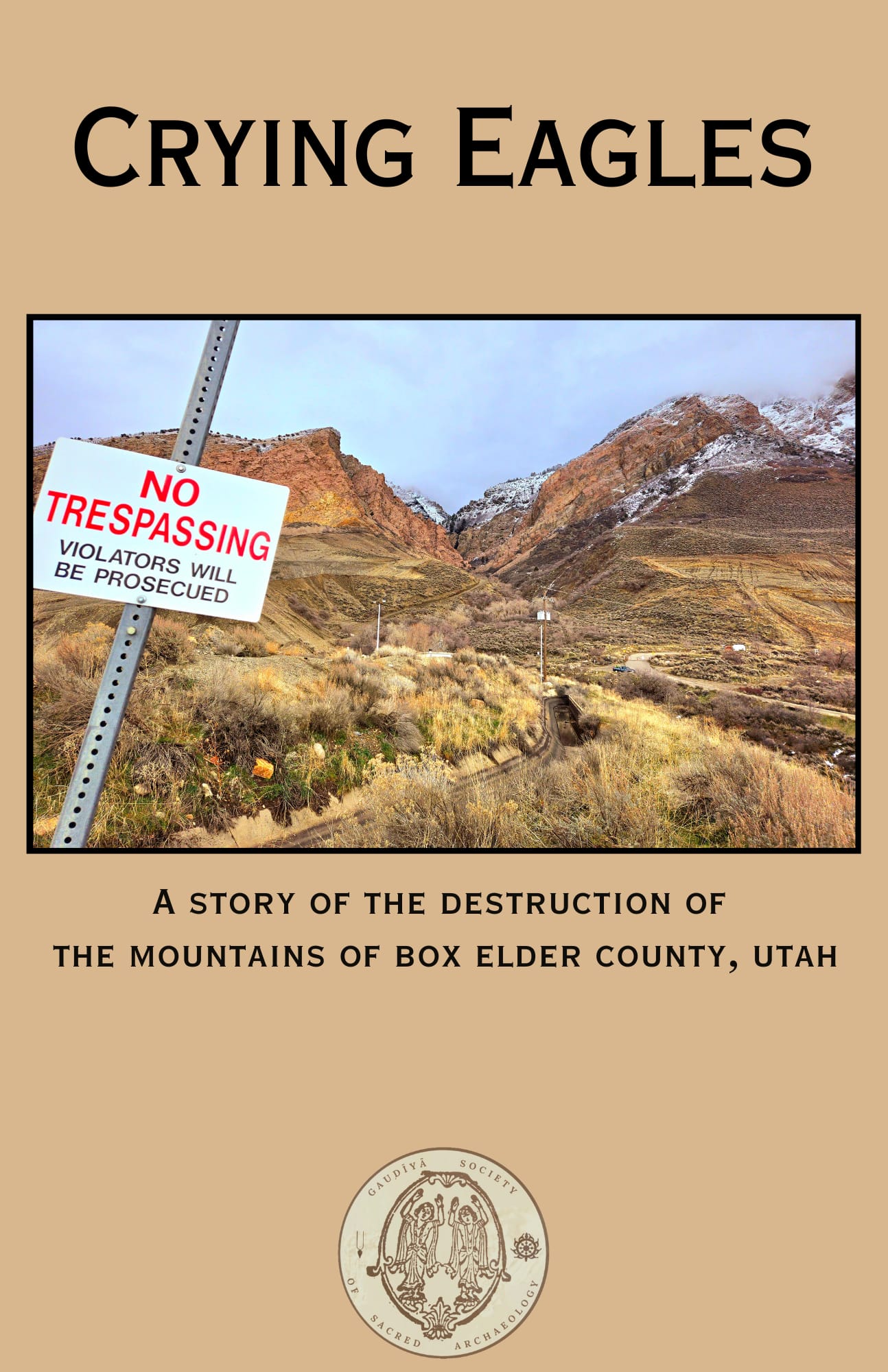

In this systematic presentation, the Gauḍīya Society of Sacred Archaeology is seeking to speak on behalf of the mountain ranges in Box Elder County that are currently being destroyed by the destructive process of sand and gravel mining, often referred to as open-pit or surface mining. Box Elder is situated in the northwestern corner of Utah, bordered by Idaho to the north and Nevada to the west, encompassing a diverse landscape that ranges from the Wasatch Mountains to the vast stretches of the Great Salt Lake Desert. This county is home to eight prominent mountain ranges, which are characterized by their towering peaks, deep canyons, and significant elevations. These ranges provide extensive habitats for a diverse array of wildlife. In contrast, other mountains in the county are flatter, with lower elevations, lacking vegetation and striking geological features. The major mountain ranges in Box Elder include the northernmost tip of the Wasatch Range, the Bannock Range, the Grouse Creek Range, the Raft River Range, the Promontory Range, the Hogup Range, the Newfoundland Range, and the Pilot Range. Out of these eight ranges, four are subjected to open-pit mining and public access loss. We will discuss all four of these ranges, but our primary focus will be the Wasatch Range, or in Sanskrit what is known as kula-acalam: the principal mountain range. The final 30 miles of the Wasatch Range, which graces Box Elder, unfolds into an expanse of breathtaking beauty, marking the range’s northernmost point in the state. The Wasatch Range’s western face is known as the Wasatch Front, and the eastern face is called the Wasatch Back. Just along the Wasatch Front alone, there are twenty active and inactive open-pit mining operations strung along the mountain foothills, which is a whopping average of an open-pit every 1.5 miles. Box Elder County is home to approximately 65 open-pit mines, both active and inactive. This makes it one of the highest concentrations of open-pit mines in the world by quantity, though not by size. The number of open-pit mines in the county continues to grow, likely making it the largest concentration of open-pit mines on Earth. Discussing all of them would make this book excessively voluminous. Therefore, we will focus only on the open-pits located in the mountain ranges. This relentless excavation ascends further each year, and the land is systematically rezoned to support ongoing enlargement and as a result, what was once public land transitions into private ownership, progressively restricting public access. The expansion of open-pit mining operations is leading to the unavoidable destruction of the entire foothills. Furthermore, a significant portion of the mountain range, despite not currently being mined, is under the ownership of mining companies or the families who support these operations and is set to be destroyed in the future. This devastation results in the loss of public access, hiking trails, and wildlife habitats, including those of the bald eagle. It also leads to the disfigurement of irreplaceable geological and anthropological history. Furthermore, many of these open-pits are located near residential areas, posing a significant health hazard due to the airborne respirable crystalline silica dust they emit. All these elements contribute to the breathtaking beauty of the Wasatch Front, which is now directly at risk. In Box Elder County, the hierarchy appears to be: 1. Open-pit mining companies 2. God 3. Federal, state, county, and city governments 4. The desires of the public 5. The local wildlife. Although no one is truly above God, it is evident that, in practice, open-pit mining companies operate with little oversight. All levels of government are advancing unethical regulations, land sales, leases, permits, and licenses that facilitate the destruction of our mountains, allowing these companies to operate unchecked.

“You should not dig gravel without the consent of the affected community” ¹

Within this northern tip of the Wasatch Range, the specific field of focus of this literature is the portion above Willard City, a unique section of the northern tip known colloquially as Willard Mountain. Other names for this seven mile section of the Wasatch Front include the Sierra Madre (West) and the Utah Tetons. In this breathtaking section of the Wasatch Front, characterized by towering peaks and fifteen stunning canyons, the crown jewel of these canyons is Willard Canyon, formerly known as North Willow Creek Canyon. Willard Canyon, is also commonly referred to as Waterfall Canyon. In this way, Willard Mountain boasts an awe-inspiring landscape, rich in wildlife diversity and steeped in the irreplaceable history of indigenous peoples, such as the Fremont and other ancient inhabitants of the Great Basin Region. All of this is at risk of being erased by open-pit mining. Once, a place for exploring and adventure, is now private property being continuously eaten away by ever widening open-pits. “Surely the mountain ranges of Box Elder can’t be allowed to crumble and decay at the hands of men insensitive to its awesome splendor. Are we the generation that will allow the final degradation of such an irreplaceable resource? As the foothills come down, the erosion not only causes scarring for decades, but any material removed displaces the foundations of the higher mountain. How many wildlife losses, landslides, and floods do we have to suffer before we make the decision to stop undermining the mountains? Research of gravel pits located in North Salt Lake has been substantiated by Mrs. Hermoine Jex of the Salt Lake Association of Community Councils. These pits have caused so much deterioration in the area that even the commercial businesses have not been able to survive. Not enough people can live there to support the small town grocery or cafe. Twenty-five cases of cancer have been diagnosed in Sweet Town at the base of Beck Street. There are numerous other horror stories but time will not permit now, perhaps later. Many directors and employees of agencies and businesses in Salt Lake City expressed negative feelings about even driving through the Beck Street area to and from work. Among these were Jay Wooley from the Utah Travel Council and Ken Powell of the Utah State Historical Society. We are very concerned about the “Scenic Corridor” outlined on Page 21 of the Box Elder County Master Plan. Do we want to turn the Gateway to the Golden Spike Empire into an area where we will be ashamed to invite our friends, an area which will cast a shadow on our tourist trade? In our beautiful brochure published by Utah’s Golden Spike Empire, Inc., we quote, “the Rocky Mountains, with their awesome power and beauty, seem to have a calming effect on everyone who visits. In the winter, every skier etches his or her own signature on Utah’s powder and packed powder snow. The mountain valleys are dotted with clear blue lakes fed by streams from winter snows. Fish and wildlife are as plentiful as our flowers in the summer. You’ll even sense a bit of alpine history where mountain men would rendezvous to trade furs and stories. And when autumn puts the summer to rest, the colors fulfill the promise of unique beauty found nowhere else. Local fruit growers tell of the damage dust does to the fruit crops. Dust collecting around the stems creates breeding grounds for insects and disease. Bees are unable to successfully pollinate the blossoms. It is impossible to sell dirty fruit. Extra time and spray increases their expenses. The dust problem is impossible to control to the extent necessary. In the fall, we invite everyone to our “Peach Days” festival. Do we want to turn our “fruit belt” into a “dust bowl”? A landowner has the right to the natural support of his land which is provided by surrounding land. The right to support is a natural right, inherent in the land itself, and applies to both lateral support from adjacent land and subjacent support from underlying strata. The right to lateral support is absolute and a landowner is strictly liable for any harm caused to adjacent property as a result of excavation on his land.”²

“The cost of inaction is too great”

This composition, Crying Eagles, inadvertently could also be a valuable resource for mountaineers looking to explore northern Utah, offering unique insights into the extensive hiking trails, local wildlife and striking geological features such as waterfalls, caves, arches, hoodoos, mountains, and notable peaks of the county. It serves as a comprehensive overview of the natural beauty and geological wonders of the region specifically in those places in which open-pit mining is taking place. This is all done in an effort to advocate for their protection. It’s a call to attention: observe the wonders that exist here, and witness the ongoing devastation they face. “Those of us who care enough, we have to do something”³

“Seventy percent of Utah voters prefer that state leaders place more emphasis on protecting water, air, landscapes and recreation opportunities over maximizing land for drilling and mining, according to the Colorado College State of the Rockies Project”.

The threat to our mountains is clear and present. Box Elder’s mountains are more than just a scenic spot for hikers; they are a natural treasure that deserves protection, especially from the destructive effects of open-pit mining. Yet, we often find ourselves lost in fantasies, rather than confronting the harsh reality that stares us in the face. The consequences of our inaction are dire, and it’s imperative that we wake up to this urgent issue before it’s too late. Willard Mountain’s stunning landscapes, unique biodiversity, and recreational opportunities, hold immense importance. Is this the inevitable fate we’ll allow this mountain to succumb to? Destroyed by corporate greed? Preserving these stunning landscapes means saving the habitat for the rich diversity of animals that call this place home. Protecting these mountains means saving indigenous history like pictographs. Saving this land means conserving the home for the bald eagles. The following comprehensive analysis aims to highlight the significant environmental, historical, geological, and archaeological value of this land and fight for the protection of what little remains. Even if we don’t have a chance, we should still fight to preserve our mountain ranges against all odds. The moral stance is to do the right thing, regardless of the opposition against you. Our goal is to present a compelling case against the gravel pit takeover occurring along the mountain ranges of Box Elder. This book is divided into five sections:

Section 1: The Gravel Pit Take Over

Explore the endangered mountains of Box Elder County, where open-pit mining poses a significant threat. This section examines the distinctive geological features and rich historical significance of each range, emphasizing the natural beauty and indigenous history at risk.

Section 2: The Inauspicious Fruits of Open-Pit Mining

Uncover the devastating effects of open-pit mining on ancestral lands, ecosystems, and communities. This section provides a stark look at the environmental and social costs, from habitat destruction and air pollution to the psychological impacts on local residents.

Section 3: Our Sacred Duty

This section offers a compassionate and transcendental perspective on environmental stewardship, emphasizing the importance of preserving natural habitats for future generations and our moral responsibilities to protect the Earth.

Section 4: The Positive Alternative

Discover sustainable alternatives to open-pit mining in the mountains of Box Elder by sourcing aggregate from alternative deposits. This section presents innovative solutions, such as transforming Willard Mountain into a nature preserve, and explores the economic and environmental benefits of these alternatives.

Section 5: Appendixes

A collection of supplementary materials, including historical documents, reports, and ordinances, providing additional context and supporting evidence for the book’s arguments.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.